More Disastrous Colorado Ballot Questions

As Colorado legislators continue to discuss property tax relief, conservative and anti-tax groups are planning disastrous 2024 ballot measures that could undermine that work. Their proposals would ask voters to create property tax revenue caps that also include cuts to assessment rates.

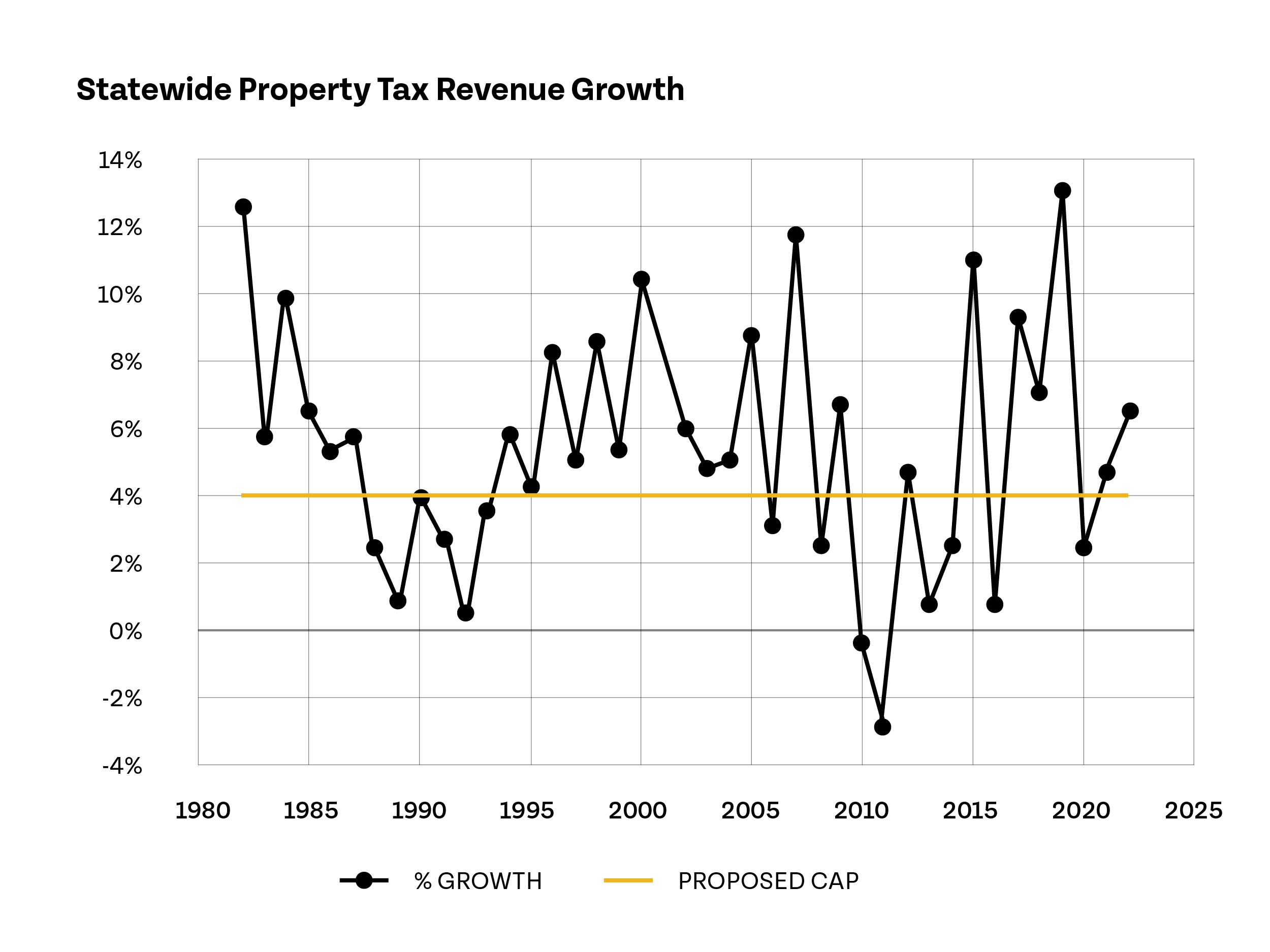

Initiatives 198-200, proposals from conservative groups Colorado Concern and Advance Colorado, would require voters to approve the retention of statewide property tax revenue that exceeds 4 percent over the preceding year, and reduce residential and commercial assessment rates from 7.15 to 5.7 percent and 29.1 to 25.5 percent, respectively. In addition, $55,000 would be exempted from residential assessment values.

The three potential ballot measures differ in how the state government would have to fill in gaps in local government funding due to the steep reduction in Colorado property tax revenues. These initiatives are the most extreme yet in this multi-year property tax war. Given the deep pockets of the proponents, these measures should be taken seriously.

Under Initiative 198, local governments are backfilled from the General Fund without reducing the TABOR surplus. Under Initiative 199, local governments are backfilled from the General Fund “up to the maximum amount practicable” without reducing the TABOR surplus. Under Initiative 200, local governments are backfilled up to $750 million from the General Fund without reducing the TABOR surplus.

None of the three potential ballot measures make changes to the State Education Fund. Colorado is projected to have $1 billion in revenues over the TABOR cap that cannot be used to invest in communities. Importantly this money cannot be touched to backfill local governments and schools if these measures are passed. The revenue loss would have to come from the base of the General Fund, impacting crucial programs and forcing cuts to childcare, health care, higher education, and even transportation.

If these measures were to make it to the ballot and pass, Colorado property tax revenues would be capped, severely limiting a vital funding stream for local services. Much like the disastrous Proposition 13 passed in California in 1978, fiscal losses could grow yearly. Initial losses in 2025 would be $2.8 billion, but they quickly compound as the baseline has been permanently reset, and gains can never exceed 4 percent.

The assessment rate cuts would create lasting reductions, cutting property tax rates and pushing off the impact of the cap. Due to the property market’s cooling from its June 2022 peak, the property tax cap would likely not take effect for an assessment cycle or two. If, for example, growth rates pass 4 percent in the 2028 assessment, it will be from an already lowered baseline due to the assessment rate cuts of the previous assessment cycles, redirecting even more state funding to local governments.

Does Colorado have a property tax? A glaring problem with these potential ballot measures is that Colorado has no statewide property tax. Property taxes are local taxes levied by over 3,500 districts around the state. Schools, fire stations, and water districts are among the most common, and each relies on its own tax to generate the revenue that provides public services and investments. Cutting across each district’s diverse needs to set a 4 percent cap would be administratively burdensome, if not impossible. A cap would force another Colorado state mandate upon local communities, much like TABOR.

Imagine a district in Lamar experiencing negative growth, but a Lakewood district sees double-digit growth. Combined, the two districts are over the 4 percent cap. What happens? These communities with different needs and economic conditions would be subjected to the average between them. Each district would have to adhere to the arbitrary cap. That shouldn’t happen. The Lakewood district might have already budgeted for a higher growth year to pay for changes or improvements in services.

Furthermore, a 4 percent cap doesn’t keep pace with inflation. In recent years, this cap would amount to a negative revenue growth mandate as inflation has risen well above 4 percent. In more normal times, a 4 percent cap after inflation becomes a 2 or even 1 percent cap. This hardly allows for governments to maintain existing services, let alone respond to public demands for new and/or increased services.

Initiatives 198-200 would have highly negative effects over time. Since 2000, the average growth in property tax revenue has been 6.5 percent. However, that growth has come in peaks and valleys with changing economic times. Crucially, changes in property values have been allowed to accumulate and grow.

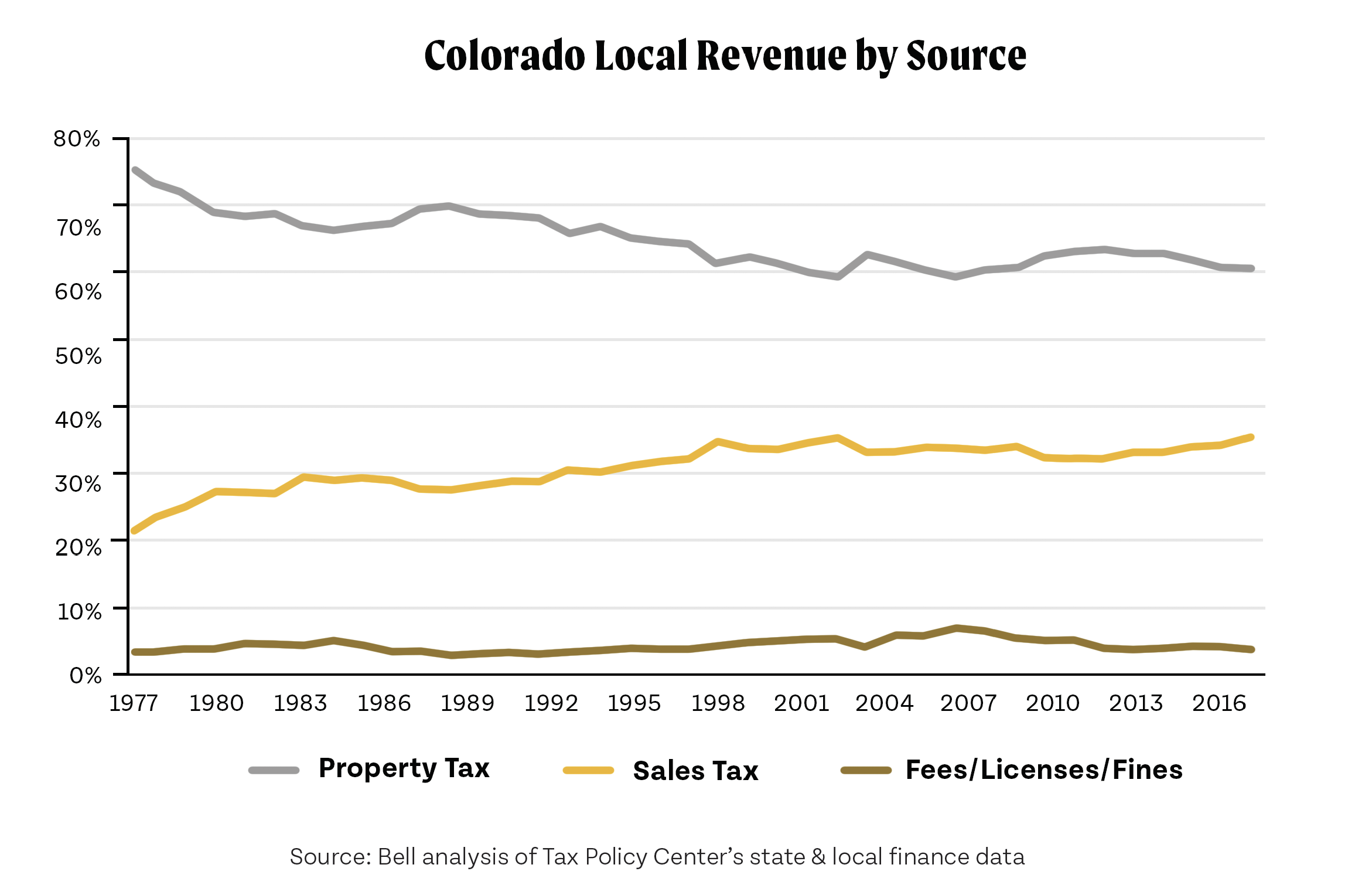

These measures would require the state to cut expenditures to backfill property tax losses. Local governments, in turn, could struggle to raise mill rates – the tax rate set by local districts – to meet funding needs. With difficulties raising property taxes, cities and counties could only use more regressive forms of taxation, like sales taxes or even fines and fees, to increase revenue, further distorting the tax code.

These measures would drastically change Colorado’s local funding system in ways that trickle up to the state. The cut-and-cap approach severely hobbles funding for the services local governments provide. This takes decisions out of the hands of constituents and allows special interest money to set the terms of the debate. Also, with the state being forced to backfill as a result of the cuts to assessment rates and a cap on growth, it is likely that the state would have to drastically cut back on spending for childcare, health care, public safety, and transportation, further eroding our already inadequate public services. These initiatives are neither fiscally smart nor fiscally responsible, and the consequences for local and state budgeting in our state would be disastrous.