Colorado’s Universal Preschool Program

Colorado’s Universal Preschool Program

In the fall of 2023, due to the new Universal Preschool Program (UPK), every child who is 4 years old in the year before starting kindergarten can attend 15 hours (half day) of fully-funded preschool in Colorado. UPK is crucial to increasing the availability of early childhood education. Access to quality child care is correlated with higher academic outcomes, a higher likelihood of graduating high school, and higher earnings in the workforce. By reducing barriers to child care and early childhood education (ECE) in Colorado, UPK is helping to set up our children, workforce, and economy for success.

It is important to remember that UPK exists within a larger ECE and child care ecosystem in Colorado. Funding for ECE varies across the state and depends on the community and its resources. While UPK is a step toward equalizing access to quality childhood education and care, it will have a greater impact in certain regions until Colorado addresses the systemic challenges facing the entire ecosystem, including funding and workforce shortages. This analysis will look at how UPK fits into the larger childhood education structure, the program’s predicted impacts, and the continuing challenges within the child care ecosystem.

How UPK Will Work

Colorado voters in 2020 passed Proposition EE, which increased taxes on cigarettes and nicotine. It funded UPK, in part, and allows children in the year before kindergarten to attend at least 15 hours of free preschool per week. A child with additional qualifying factors, such as household income, need for an individualized education program, dual language learner, housing status, and foster/kinship care, is eligible for an additional 15 hours, totaling 30 hours. Three-year-olds with one or more of these qualifying factors are eligible for 10 hours of preschool a week.

UPK funds will go to licensed, registered providers who care for children enrolled in the program. Almost 1,600 providers have registered, out of the total 2,184 licensed providers in the state. Collectively, these providers can offer approximately 62,000 UPK seats. The numbers continue to increase as more providers and school districts register for the program. However, the number of seats available will fluctuate as the registration process is streamlined.

Families may choose from various settings available to them such as home care, center-based care, or public schools that offer care for preschool-age children. This allows families, based on their needs, to choose providers that are most convenient and most desired.

UPK Impacts: Affordability and Accessibility

Major barriers to child care in Colorado, and nationally, are affordability and accessibility. Affordability refers to the relative cost of care while accessibility refers to the availability and supply of care. UPK can positively impact both factors by decreasing costs and incentivizing providers to offer additional care. As the system currently stands, child care absorbs nearly 30 percent of median household income for Colorado families. UPK is well suited to begin addressing this barrier. By providing at least 15 hours of free preschool to 4-year-old children across the state, families each are projected to save an average of $6,000 a year. Affordability also affects accessibility by expanding the reach of ECE to children of families earning low incomes who were not receiving licensed care due to cost.

In terms of accessibility, UPK has so far been successful in reaching providers across the state with at least one UPK provider in every county. With the current number of registered providers, there are an estimated 60,000 UPK seats offered, an impressive number in the program’s first year of implementation. Compared to Colorado’s 2023 population projections of 63,000 4-year-olds, this is promising in efforts to supply the needed amount of care. However, the estimated 60,000 seats offered could be an overestimate as Colorado Department of Early Childhood (CDEC) refines its data tracking and provider registration. This is, nonetheless, confidence-inspiring for the future accessibility of UPK.

These high rates of participation by providers are partially due to CDEC’s provider reimbursement rates. CDEC calculated provider rates using a base cost of high-quality care, adjusted for personnel costs (including salaries and benefits), regional cost differences, local cost of living, local poverty level, geographic factors, and inflation. Providers have applauded these reimbursement rates for their adequacy in covering the actual costs of care.

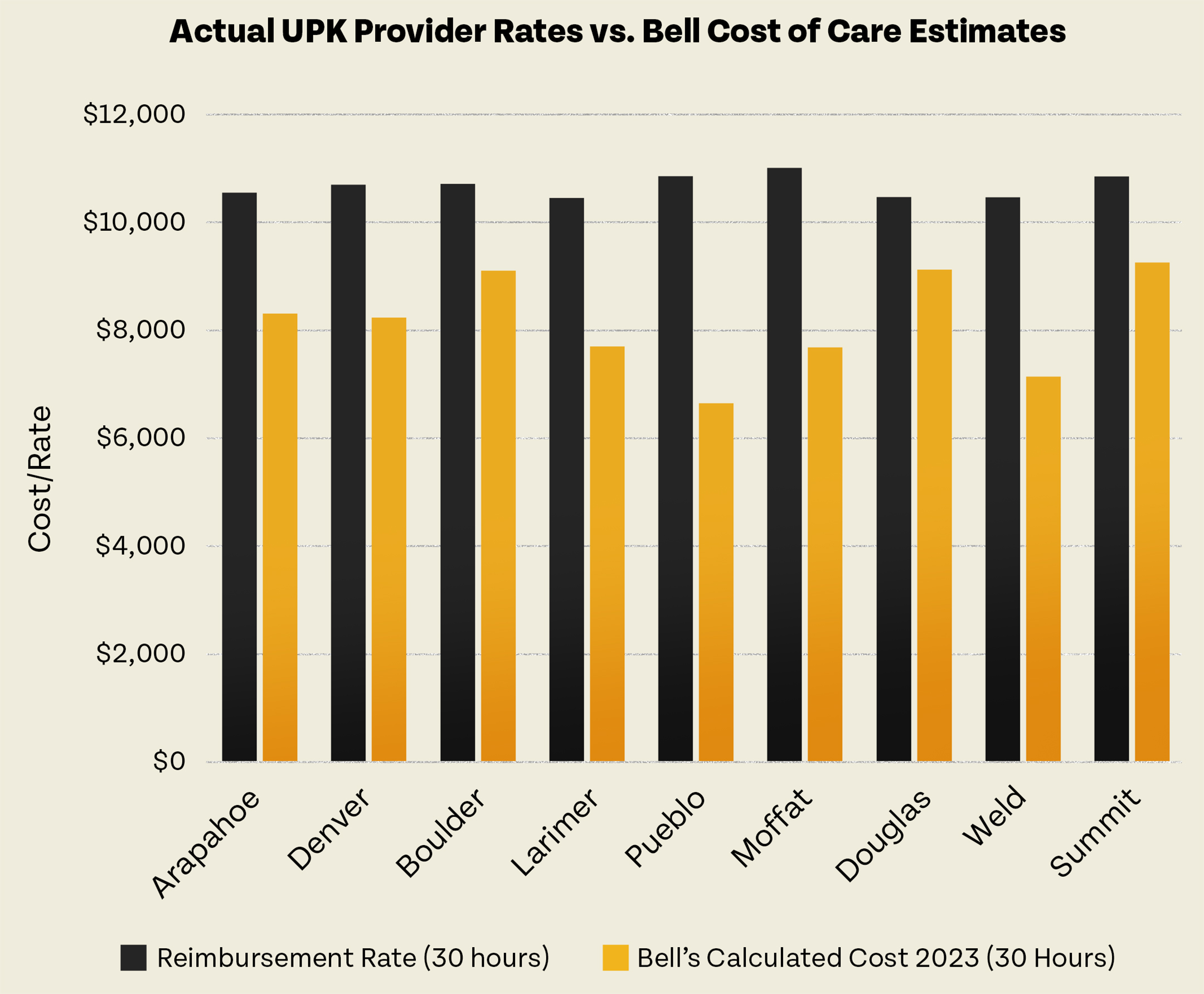

The graph below shows the actual UPK rates paid to providers compared to cost of care estimates from the Bell’s cost of care model in select counties. Calculations from the Bell are inclusive of the cost of providing care for 4-year-olds receiving high-quality care in centers, and workers receiving a self-sufficiency wage.

It is notable that the provider rates from the state are higher than the Bell’s calculated costs of care. Partially accounting for this difference is that CDEC incorporated local poverty levels in calculating their poverty rates, and included a quality improvement factor. A quality improvement factor, as the name implies, is meant to help providers with resources to increase their quality ratings with the state. The Bell’s cost model does not include either of these factors. Finally, while higher rates of inflation may also influence this difference, the bottom line is that the state offers a generous reimbursement rate that exceeds that used in the Bell’s cost model.

It is critical to have sufficient reimbursement rates to incentivize higher provider uptake, which increases the accessibility of UPK slots across the state. Given the existing shortage of child care workers in Colorado and the associated limited accessibility of child care, adequate provider rates may help ensure early childhood educators are paid a fair wage, assisting in recruitment and retainment of child care workers.

The ECE Ecosystem in Colorado

UPK does not exist in a vacuum. Instead, it contributes to an extant system of interconnected federal, state, and local programs. Parents in Colorado can simultaneously use publicly-funded programs such as Head Start, Early Childhood Special Education, Colorado Child Care Assistance Program, and now UPK to help cover the costs of preschool. Some counties, cities, and districts raise additional money for early childhood education. HB19-1052, which provides for Early Childhood Development Special Districts, was passed in 2019 and allows for the creation of special districts for the express purpose of funding early childhood services. While no new special districts have yet been created as a result of this legislation, the bill may lead to increased regional funding in the coming years.

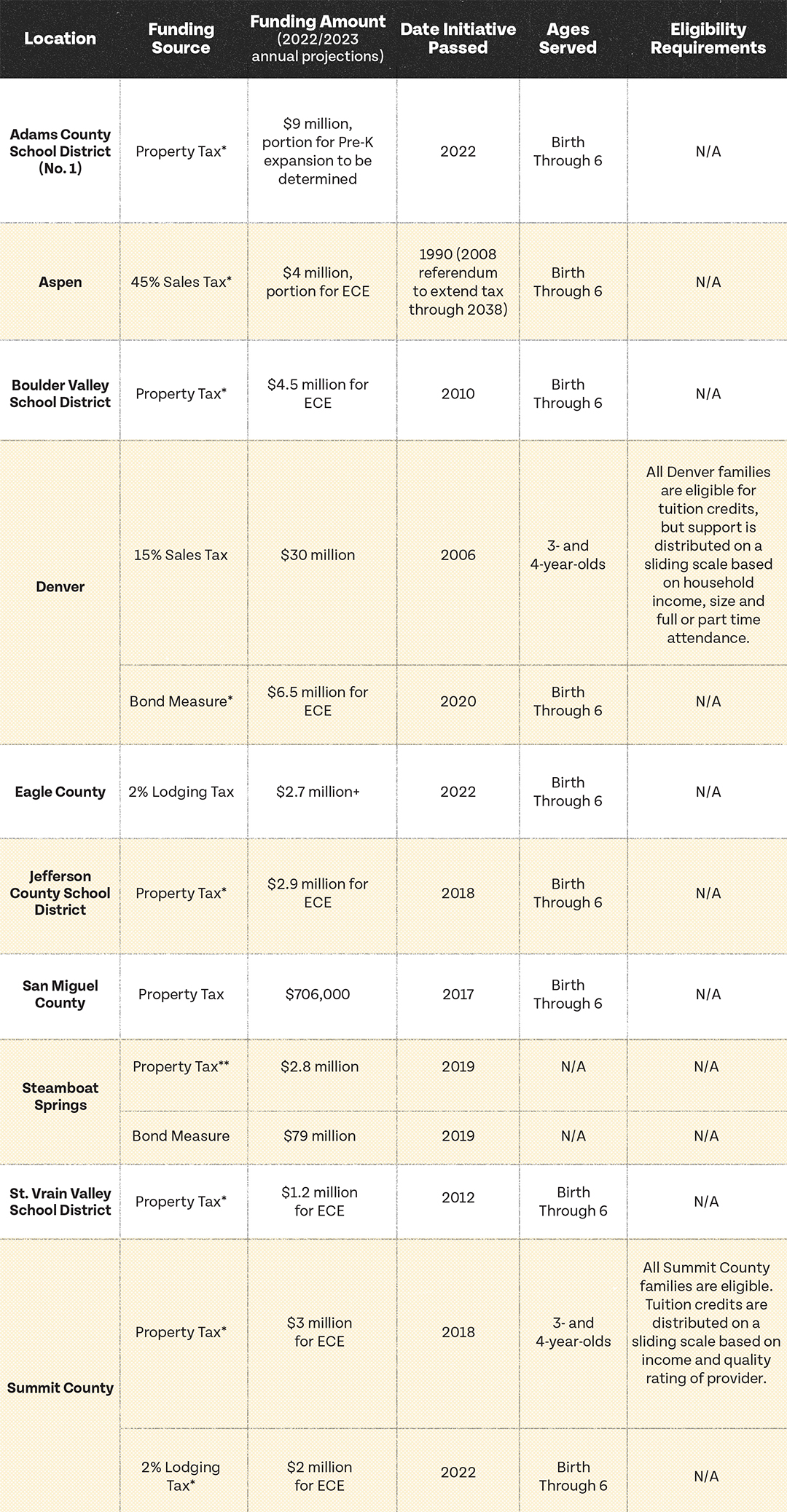

Several cities and counties have developed new, local funding streams to support ECE, but to varying degrees. Creation of these revenue sources depends both on voters and the relative wealth of residents in a community, as local funds are often raised through property taxes. The reliance on local property taxes can produce regional inequities since, for example, one mill in a district with low property wealth may only raise $4,000 while a property rich district can raise up to $13 million with one mill. It also depends on whether voters are tax averse. A combination of these factors allows certain districts or cities to advance ECE significantly more than others. In Denver, for example, voters agreed in 2006 to pass a sales tax to fund the Denver Preschool Program and in 2021, the program partnered with over 250 providers and offered 4,818 children tuition assistance in Denver. The table below shows the cities, school districts, and counties that have raised taxes for the express purpose of ECE, and their relative dollar amounts.

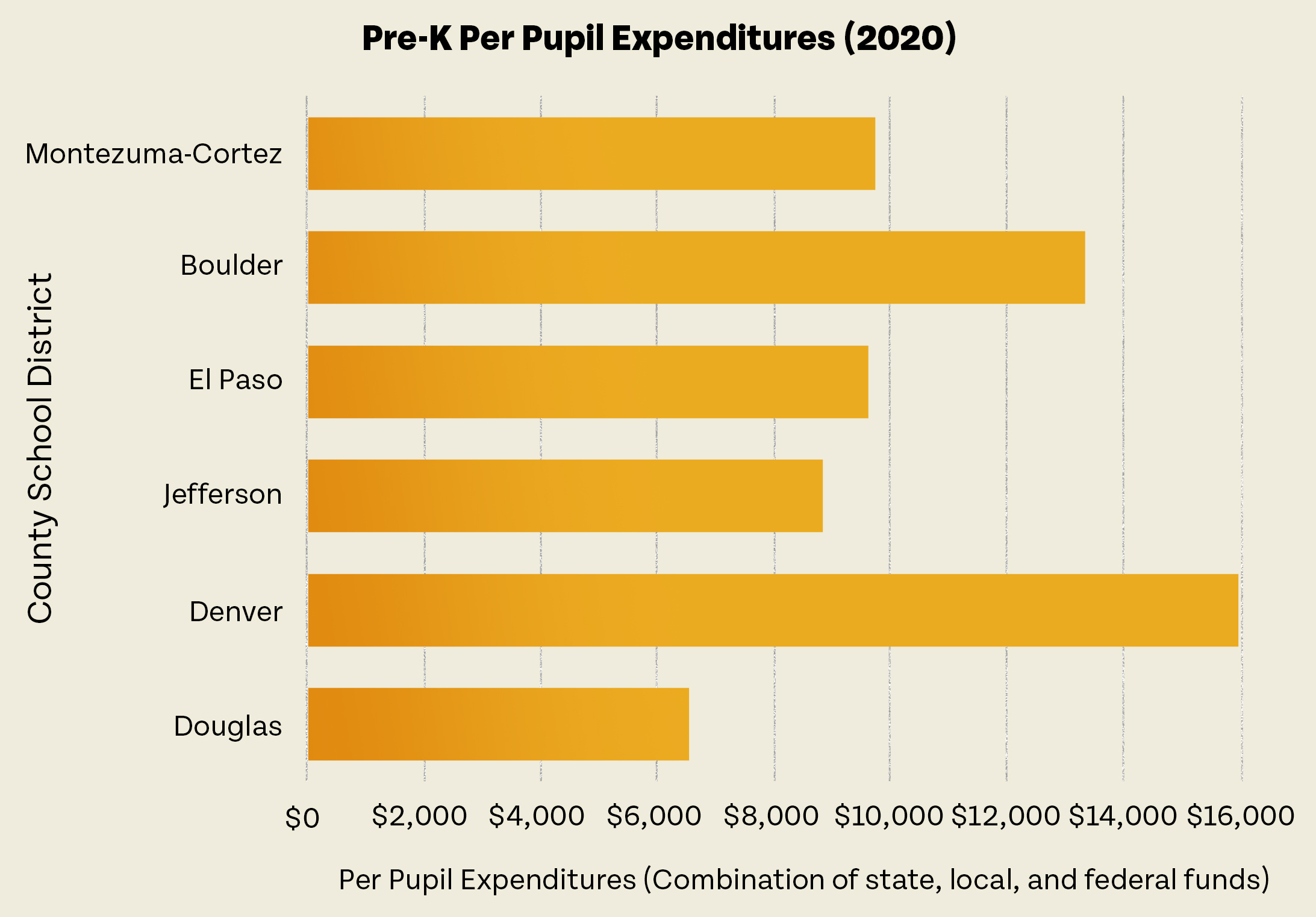

These counties and school districts will have access to an additional pool of funding for ECE not seen in all parts of the state. Whether the funds are used for paying early childhood educators more, purchasing new classroom materials, or serving more children, certain districts will be able to offer more. The graph below illustrates the differences in public, per pupil spending for pre-k students in the public school system in Colorado. These differences may be due to relative wealth differences of the school districts as well as decisions by voters to increase revenue.

Ongoing Challenges

Though a new, important, and promising program, UPK alone is not the cure for Colorado’s child care crisis. Instead, the overall ecosystem remains challenged by a worker shortage, uneven funding, and disparate access to care. To create a stronger ECE ecosystem, these challenges are important to consider moving forward.

Accessibility of Infant and Toddler Care

As highlighted above, elements of Colorado’s childcare system are tightly interconnected. Notably, these interconnections apply to the availability of childcare across age spectrums. Advocates have raised specific concerns regarding UPK’s effects on the accessibility of infant and toddler care in Colorado. It is most expensive to provide infant and toddler care, and there is less availability. To help cover the cost of providing care for infants and toddlers, providers will often also provide less costly care for 4-year-olds. UPK is a voluntary program and there are concerns it may pull 4-year-olds from providers who are not participating in the program. This, in turn, may make infant and toddler care economically difficult for some providers to offer. This situation highlights the need to continue focusing on sustainable funding options for children of all ages.

Geographic Accessibility

Nearly 50 percent of Coloradans live in child care deserts. These deserts are more likely to exist in rural and low-income areas. In order to achieve their full potential, UPK and other child care programs must be paired with efforts to reduce geographic disparities in access to care.

In 2020, Governor Polis signed into law HB20-1002 which created two new grant programs. One of them, the Emerging and Expanding Child Care Grant Program, helps providers start or expand their child care business, particularly in areas considered child care deserts. Applications for the grant program opened in early 2021. In addition, the substantial provider rates offered by UPK may help incentivize more providers to open. However, it will likely take a few years to see the effect. Until then, UPK and other public programs will only increase affordability and accessibility for families who have nearby child care options.

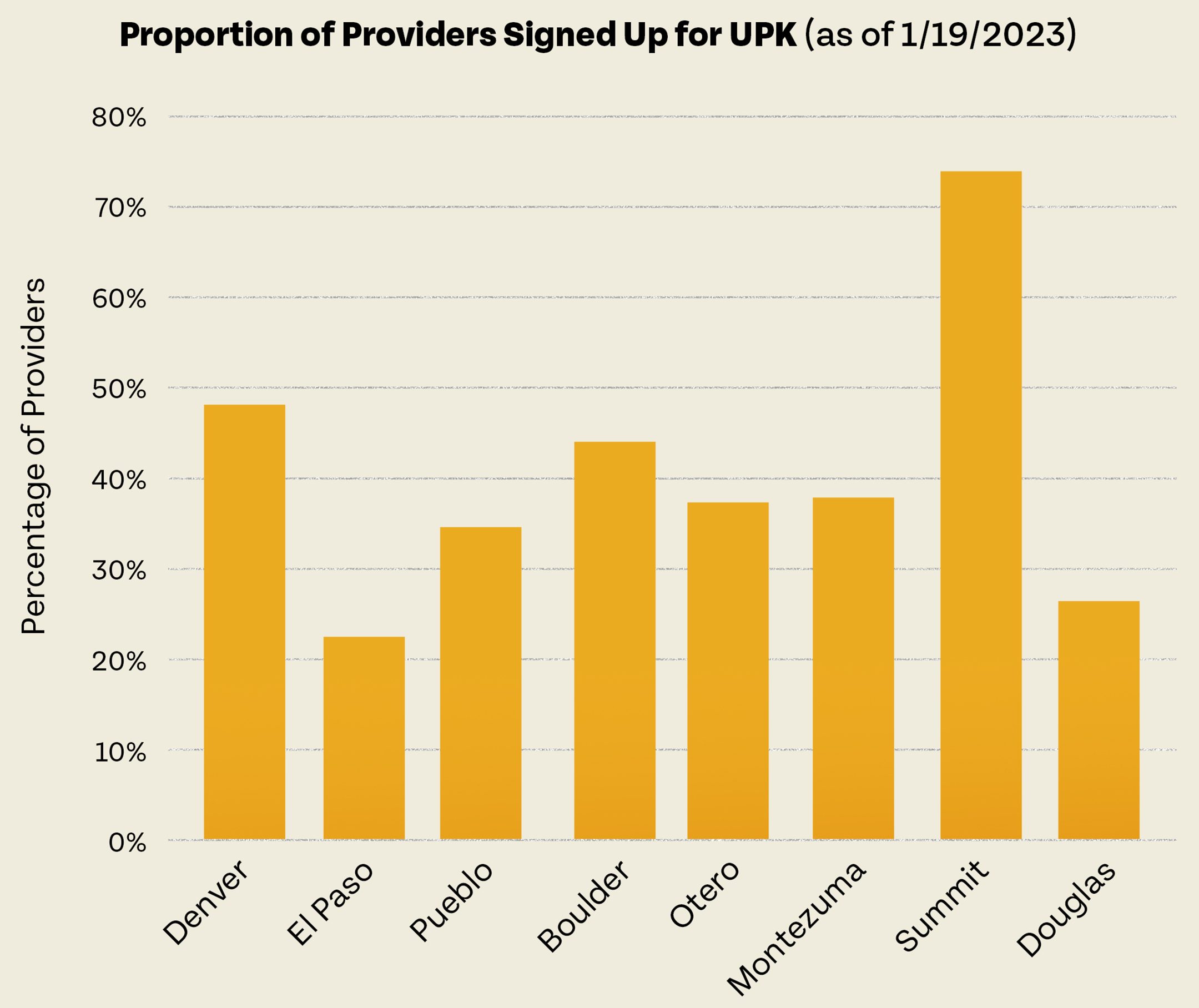

Specific to UPK, which is a voluntary program, there are concerns that providers may not register for UPK equally across regions of Colorado. The graph below shows the proportion of licensed child care providers (with preschool aged capacity) that have signed up for UPK as of Jan. 19, 2023.

Providers are continuing to sign up every day, and therefore the data is constantly evolving, and no definitive conclusions can be made about who will have access to UPK seats until the school year starts and registrations are complete. However, currently every county has at least one provider signed up through the UPK program. What is notable, however, is the large variation of providers signing up for UPK across counties in Colorado. For example, in Denver County, almost half, 48 percent, of licensed providers have registered for UPK and 75 percent of providers in Summit County, while in El Paso and Pueblo Counties, only 22 and 35 percent, respectively, have registered. This does not translate to the number of actual seats these providers will have available but shows that there will likely be regional differences in access to UPK based on providers’ decisions to participate. Again, given the adequacy of provider reimbursement rates, we will likely see an increase in the number of providers registering for UPK, and this is something to look out for in the coming years.

The Need for Flexible and Full Time Care

With limited child care availability and long waitlists, parents will often resort to a patchwork of care arrangements to meet their needs. This includes relying on relatives, babysitters, and other informal family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care providers in supplement to or in place of licensed care providers. This is especially true for parents who work nonstandard hours (work hours outside of 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays.) Nationally, 43 percent of children under 18 have a parent working non-standard hours and only 8 percent of center based ECE providers and 34 percent of licensed home-based providers offer care during nonstandard hours. Additionally, licensed providers may only have the capacity to provide part-time or half-time slots while parents may need full-time care, causing them to search for multiple arrangements. The instability of relying on multiple care arrangements is linked to reduced school readiness, and negative language, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes.

For those who will be able to access UPK, these challenges still exist. They will receive 15 hours of fully-funded preschool, for nine months out of the year. But this still leaves in question the other 35 hours per week and the remaining three months of the year for full-time working families to sort out. While the state considers 30 hours a week full-time, Bell measures full-time as 50 hours a week. This is because if parents are working full-time, that more realistically looks like 40 hours a week, with additional buffer time for drop-off and pickup. With limited UPK hours, parents will still have to address a patchwork of care arrangements and struggle to secure stable care for their children.

In a study done by the University of Chicago, researchers found that moving from half-day to full-day preschool programs increased student enrollment and attendance. Increased availability of full-time care and flexible hours would allow for more stability for parents and families, affecting their ability to participate and remain in the workforce, and reach families and children that are more likely to rely on informal care. That would result in positive learning and development outcomes.

What About Informal Care?

Additionally, many public funding options, including UPK, are only available to licensed providers. Apart from the qualified exemption in Colorado Child Care Assistance Program, FFN providers are not eligible for available funds, and therefore, those relying solely on FFN care will not be able to take advantage of UPK. FFN care is more frequently relied upon by low-income families and those with nonstandard hours. As families of color are overrepresented in both of those categories and are more likely to seek culturally responsive care, FFN care is also more often utilized by families of color. Families may choose FFN care based on preference or because it is more flexible and convenient for scheduling. However, it often is the only option for families due to limited availability and higher cost of licensed providers.

In the case of a program like UPK, children can attend a licensed facility for just the 15-plus hours a week and return to their FFN providers for additional hours. But this causes instability in providers and classmates for a child learning to make connections and grow socially and emotionally, with negative effects for their development and growth.

FFN providers are a critical component of Colorado’s child care ecosystem. However, they are often overlooked in many publicly-funded programs. Identifying and implementing stronger solutions to support these providers and the families who rely upon them will only create a stronger child care system.

Conclusion

UPK is a program to be celebrated and has had an impressive rollout to date. It has the potential to decrease child care costs and incrementally increase accessibility. But UPK will have its greatest impact when we holistically address the inequitable funding and the inaccessibility of care options in Colorado. By thinking broadly about the interconnected nature of the child care system and centering the needs of impacted families and workers, we can make progress to support a stronger Colorado.