Prop 117 is Bad for Colorado’s Democracy

Proposition 117 and enterprise funds can be confusing. The Bell Policy Center developed an overview of enterprise funds (the focus of Prop 117) and their functions, while the 2020 Ballot Guide goes over the actual measure in great detail. Even still, there are large consequences of Prop 117 that are just under the surface and are important to understand as you vote.

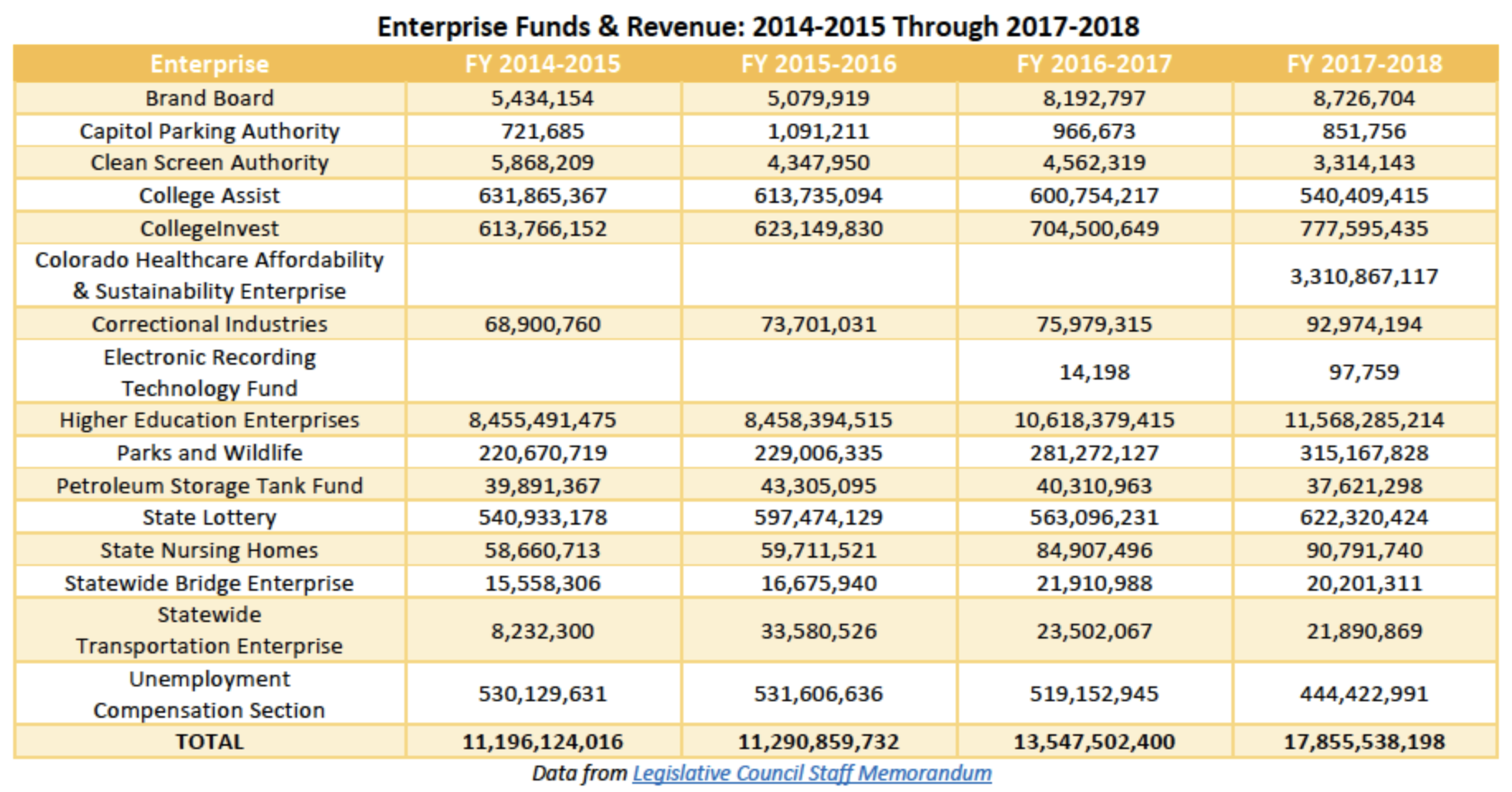

Enterprise funds have become an important tool in funding services in Colorado. Health care programs, air pollution control, higher education tuition, transportation projects, state parks, and other programs Coloradans rely on are funded and provide for through enterprise funds. Enterprise funds were specifically created through TABOR in 1992 and were intentionally exempt from provisions of TABOR, such as voting requirements and the larger revenue cap on the state’s General Fund. Enterprises, which are government-owned businesses that have revenues not subject to the General Fund revenue cap, have filled indispensable gaps in our state’s public services.

But what would likely happen if Proposition 117 passes could be very destructive to the democratic process in Colorado. Prop 117 would put creation of enterprise funds to the ballot instead of allowing our elected leaders to do what they find necessary to preserve and improve public services in our state. As we know, and have greatly learned, whenever a question is on the ballot that could affect business’ bottom line or may charge polluters to address the consequences of their actions, dark money and special interest groups flood in to protect corporations’ pockets.

Let’s use current enterprise fund as an example: The Petroleum Storage Tank Fund is an enterprise fund that would be subject to a vote of the people if Proposition 117 had been in place when it was established. The Petroleum Storage Tank Fund is a pretty straightforward example of an enterprise fund. It covers the ongoing assessment of operating storage tanks and the cleanup of contaminated land. The funding comes from a fee on the petroleum itself, focusing the costs of cleanup on the largest contributors to the pollution.

Is there any question whether oil and gas companies would spend millions to try and make sure they no longer had to pay this fee? If business interests don’t want to pay a fee that would broadly benefit workers, would they just sit on their hands, or would they spend millions on misleading ads and mailers trying to distort the issue? Based on recent electoral history, the answer seems pretty clear.

Prop 117 would also provide voters with veto power over a fee that only a fraction of them will have to pay in exchange for a good or service. It seems patently unfair that while only a small percentage of Coloradans will have to pay tuition for college, all voters would have a say on whether that transaction (tuition for education) can happen without crowding out other public investments. Given the limited budget Colorado has to work with, sometimes it is necessary to use fees (as opposed to the General Fund) to fund important things we depend on.

For example, enterprise funds encompassing our public higher education institutions had a revenue in fiscal year 2017-2018 of $11.6 billion. The entire General Fund budget that year was just $10.6 billion. Using fees to fund higher education institutions means the revenue in the budget is also available for other important public services, like health care, K-12 education, and other vital programs.

There are many problems with Prop 117. The need to fund public services in Colorado is too acute to allow one of the few tools we have to be subject to more obstacles and tests. But the issues that would arise in an election about these complicated questions would overwhelm the actual subject at hand. Proposition 117 is a dangerous experiment for Colorado and one that would set our fiscal system back even further.