How Does Colorado’s Budget Work?

How Does Colorado's Budget Work?

The development of Colorado’s budget is a complex process in which many different parts of state government are asked to make difficult prioritization decisions. More than a manifest of where funds are directed, the final budget is a statement of our values as a state.

It’s crucial for Coloradans to better understand how their money is being spent, how these decisions are made, and what programs get funded from year to year. Too often, the complexity of this process is used to make it seem as though Colorado could and should just further prioritize its way out of large fiscal deficits. Instead, these arguments often have ulterior motives that run counter to Colorado’s values, including the need to keep the state competitive for years to come.

Below is an overview of what the Colorado state budget is comprised of and how it comes together, as well as clarity on the decisions made by policymakers. The following is aimed to help Coloradans understand how to best engage in the process, where there are gaps, and what the stakes are for the next budget.

The quick answer? The entirety of FY 2019-2020’s Colorado budget comes to about $32 billion.

But Colorado’s budget isn’t just a number. There are multiple factors to consider in understanding that amount.

On a per-capita basis and compared to the rest of the country, Colorado ranked near the middle in terms of state and local spending in FY 2017-2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Colorado’s per-capita spending is highly reliant upon local taxes versus state income taxes. As of 2015, Colorado ranked sixth in the country on the percentage of taxes coming from local sources and 44th in the amount of state taxes per $1,000 of personal income. This means the quality of public resources relies upon the locality where someone lives. This has led to great inequalities across the state, particularly for rural districts.

Of the roughly $32 billion state budget, most of those funds are already dedicated to specific programs generated by user fees. The legislature has little discretion on how these funds are used and they cannot be reallocated to other programs or state needs.

Another important aspect of Colorado’s budget is the revenue cap established in the Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR). Legally restricting the legislature to spend above it, the revenue cap — covered in greater detail in the Bell’s piece on debrucing — limits the total amount of funds that can be utilized each year. When revenue is strong, like in FY 2019-2020, this cap stops the legislature from allocating additional revenue to the growing needs across the state. The revenue cap handcuffs the legislature and makes it difficult to prioritize for state needs in strong economic years.

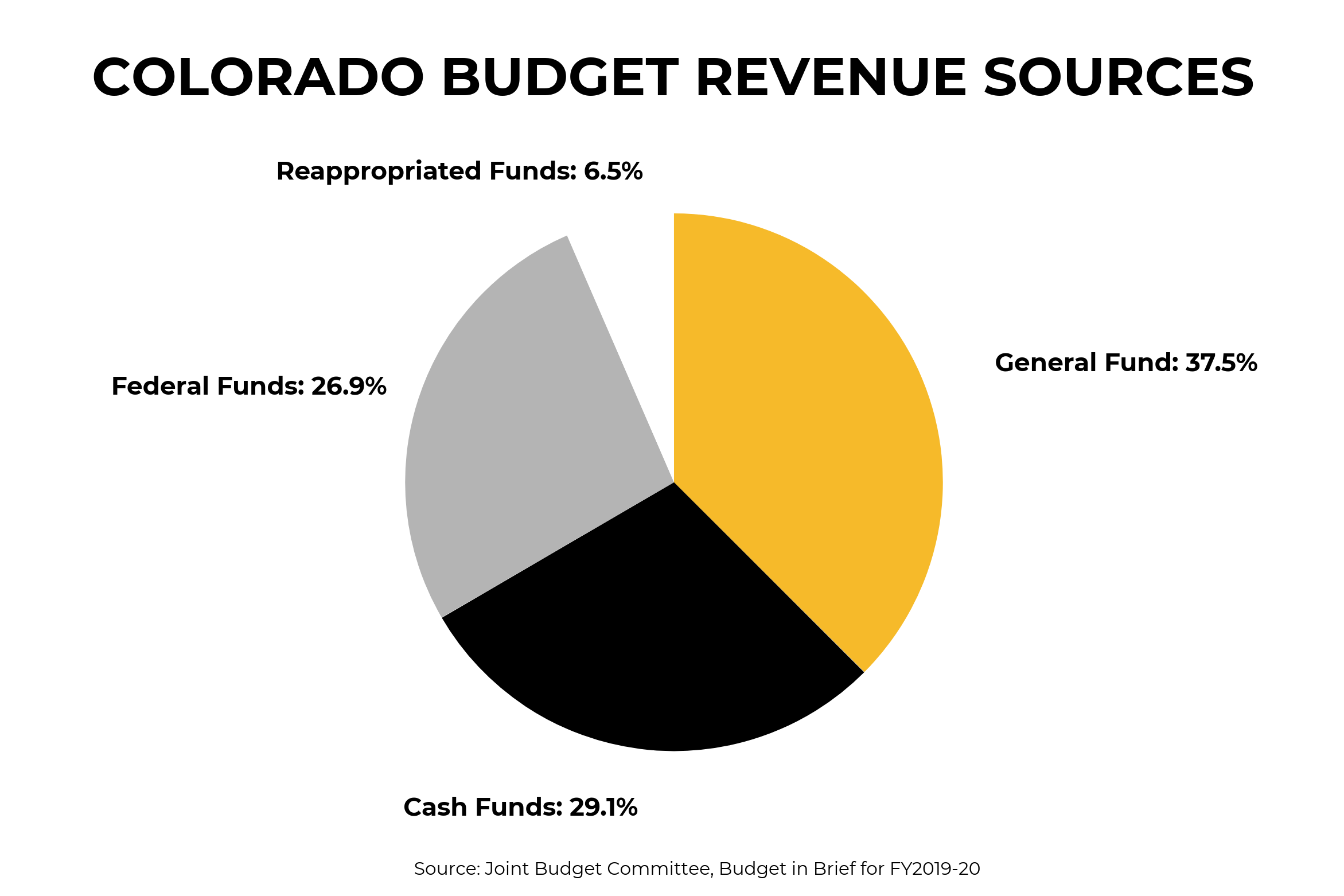

The vast majority of revenue — nearly 95 percent — in Colorado comes from three sources: taxes from residents, businesses, sales, and other places; cash funds and user fees; and federal funds. The rest comes from what are known as reappropriated funds.

While the largest portion of Colorado’s budget comes from tax revenue (a little more than $12 billion in FY 2019-2020), that makes up only 37.5 percent of the overall budget. Cash funds and federal funds make up 29 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Cash and federal funds are mostly targeted funds, going directly to certain programs without any discretion for state policymakers to steer them to other places.

This means each year there is roughly $12 billion that can be allocated to existing and new programs.

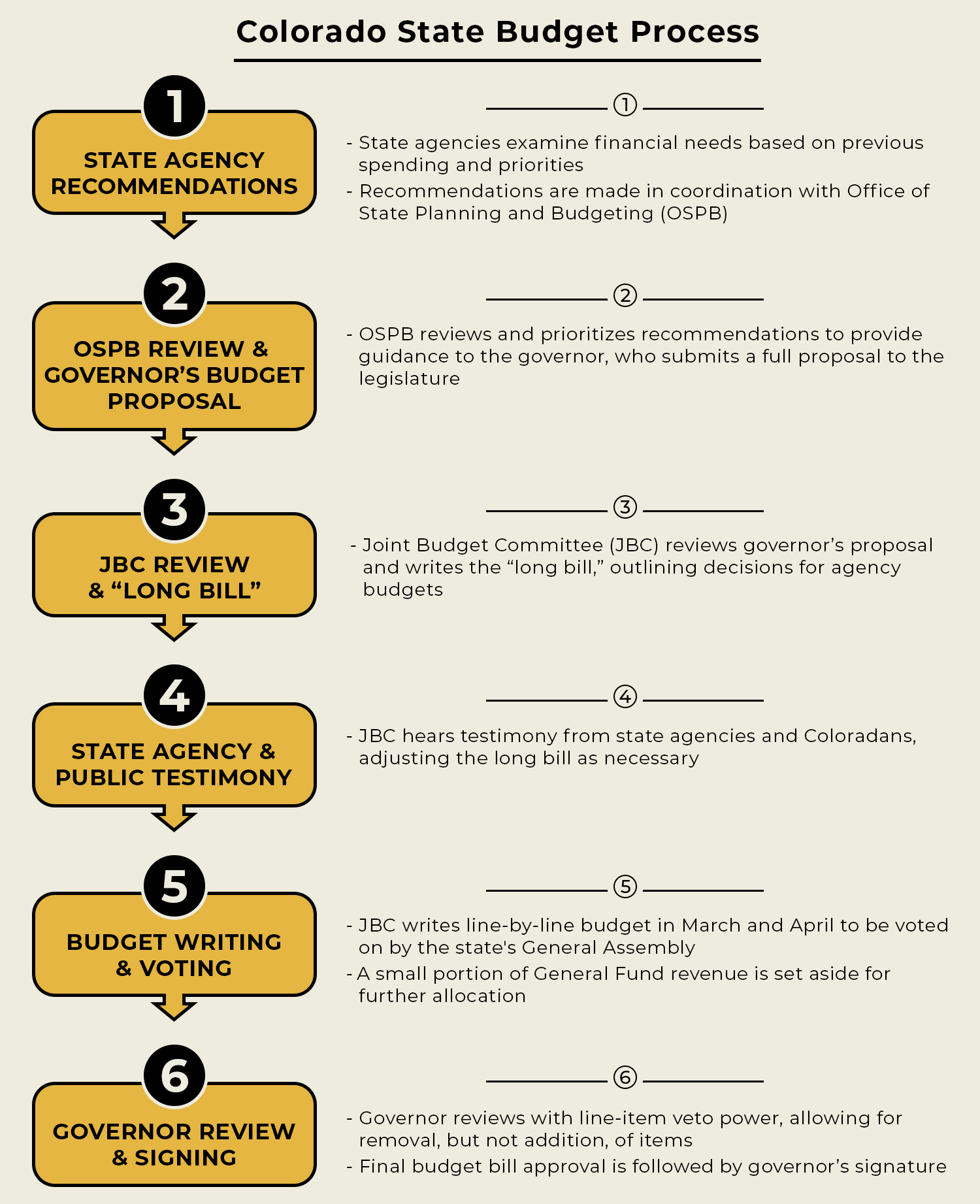

The process of writing the state budget is a lengthy one in which many actors work to prioritize their requests. Here is a basic outline of how it works:

1. All state agencies are asked to examine their existing programs, needs for current and additional programs, and increased or decreased costs in operating their programs. In coordination with the governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB), agencies make their budget recommendations based upon previous years’ performance, growing or lessening needs, and priorities within their agencies.

1. All state agencies are asked to examine their existing programs, needs for current and additional programs, and increased or decreased costs in operating their programs. In coordination with the governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB), agencies make their budget recommendations based upon previous years’ performance, growing or lessening needs, and priorities within their agencies.

2. By November, after the agencies have finalized their recommendations and presented on their justifications, OSPB examines the needs, priorities, and performance of agencies across state government. OSPB makes prioritization recommendations to the governor, who submits a full proposal to the legislature detailing recommended budgets for each agency.

3. The Joint Budget Committee (JBC) begins review of the governor’s proposal in November and uses it as a guide to write a “long bill” that outlines its recommendations and decisions for agency budgets. JBC is the legislative body whose sole charge is writing the yearly budget. It is made up of six members — three state senators and three state representatives. The majority party in each house of the General Assembly gets two members and the minority party gets one. In 2019, this means there are two Democratic senators and two Democratic representatives, with one Republican from each body.

4. As a part of their process, JBC hears testimony from all state agencies to better understand the needs of each and how to best direct funding. Through testimony, they also listen to everyday Coloradans and advocates to learn about the needs of communities on the ground. 2019 was the first year that the JBC invited any interested Coloradans to testify prior to the budget passing out of the committee.

5. During March and April of every year, JBC then writes the budget line by line and passes it out of committee to go to the state Senate and state House to be voted on by the full bodies, with few changes allowed. Based upon available funding, JBC assigns a small portion of the General Fund for further allocation by the Senate and the House. In 2019, this amount was around $620 million.

6. After complete passage through the Senate and House, the bill is presented to the governor for signature. The governor can exercise line-item veto power to strike specific spending provisions, which allows him to strike items from the budget, but not add specific items.

Specific Details of Budget Development

Each year, Colorado’s budget is based upon projections regarding tax revenue that will be received in that year. These budget projections are developed by both economists within the governor’s Office and the Legislative Council, a nonpartisan body within the General Assembly. Multiple economic and revenue projections come out over the course of the year that are based upon the most recent economic forecasts of the Colorado economy.

In December, preliminary projections are established to set a high-level understanding of how much revenue will be available during the budget process. This analysis is updated in March just as the legislature is getting ready to write the budget and becomes the baseline for budget decisions. Additional analyses come out in June after adjournment and September. The projections can vary from month to month based on changes in the economy, but the budget is set by May when the legislature adjourns for the year.

These analyses also project future years and what might be available to the budget process down the line. According to the Legislative Council, if FY 2019-2020’s budget kept appropriations for all agencies constant from FY 2018-2019, the legislature would have a total of $763 million left over to allocate to new programs. If the budget were to hold from the previous year, but with increases for inflation and population growth — a 3.3 percent change in 2019 — then lawmakers would only have $338 million to increase spending. Based upon these numbers, there is little spending growth year to year unless drastic cuts are made to existing programs.

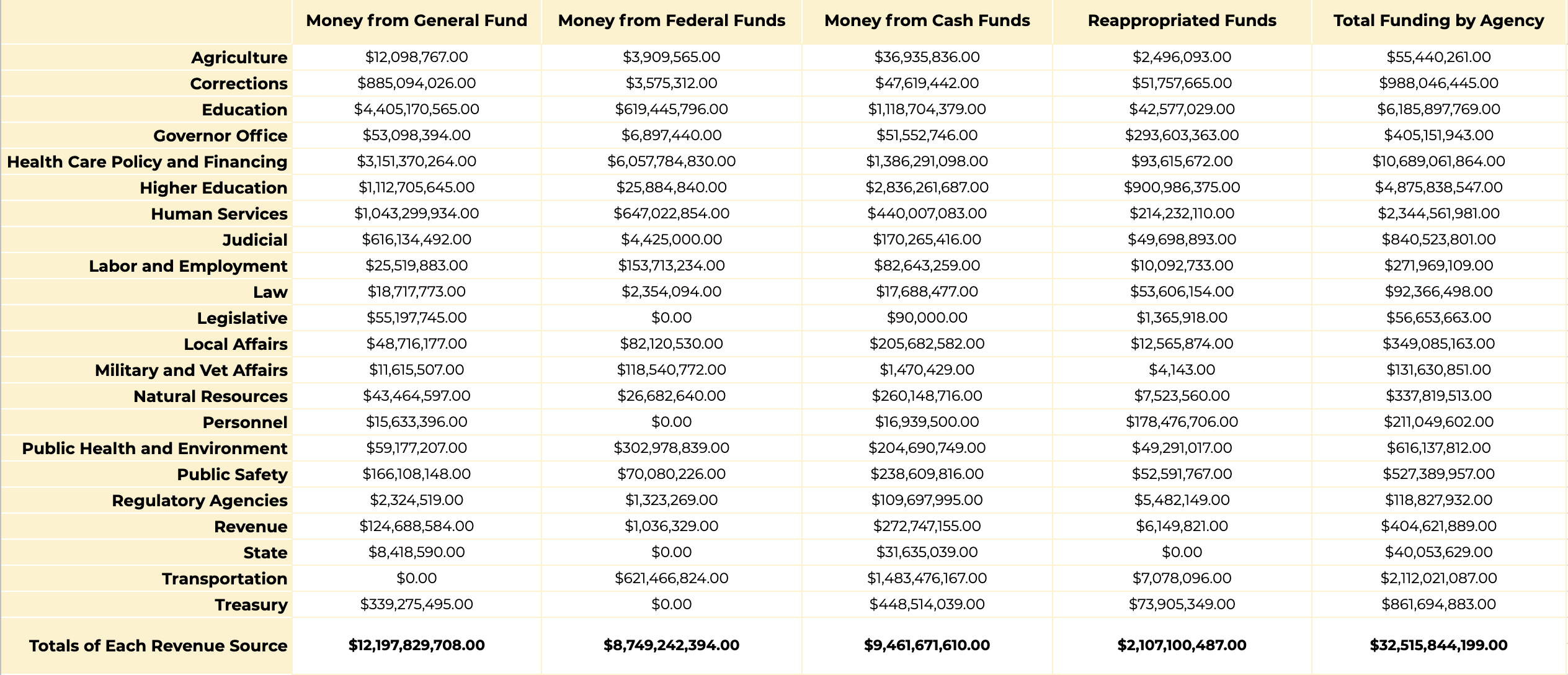

So, where do the $9.4 billion in cash funds and $8.7 billion in federal funds go? Some of this is covered in a recent Bell piece on enterprise funds. While not all cash funds are enterprise funds, they are all categorized as funds set up to provide a direct service financed by fees for that service. Over 70 percent of cash funds go toward higher education (in the form of tuition payments), transportation (through toll roads, vehicle registration fees, and driver’s license fees and fines), hospital providers (as part of a program where the federal government reimburses hospitals for Medicaid expenses), and early childhood and K-12 education (through the State Education Fund).

Federal funds are similar to cash funds in that they’re obligated for specific programs through the Congressional appropriations process. The state government has little say in much of where this revenue goes throughout the state. By far the largest recipient of federal money — nearly three-quarters of all federal money in Colorado — goes to health care, mostly through Medicaid (which the state has to match through General Fund money) and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

The other state agencies that receive the most federal money are the Department of Human Services — programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) — and the Department of Transportation, which receives significant funds from the Highway Users Tax Funds and other federal programs designed to help states pay for their transportation infrastructure.

Given 56 percent of Colorado’s budget is tied up in obligated funds, it makes sense to focus on the other parts — namely the General Fund dollars — lawmakers can direct and over which they have discretion. But even then, it isn’t so simple as to say all $12 billion dollars of the General Fund is up for grabs.

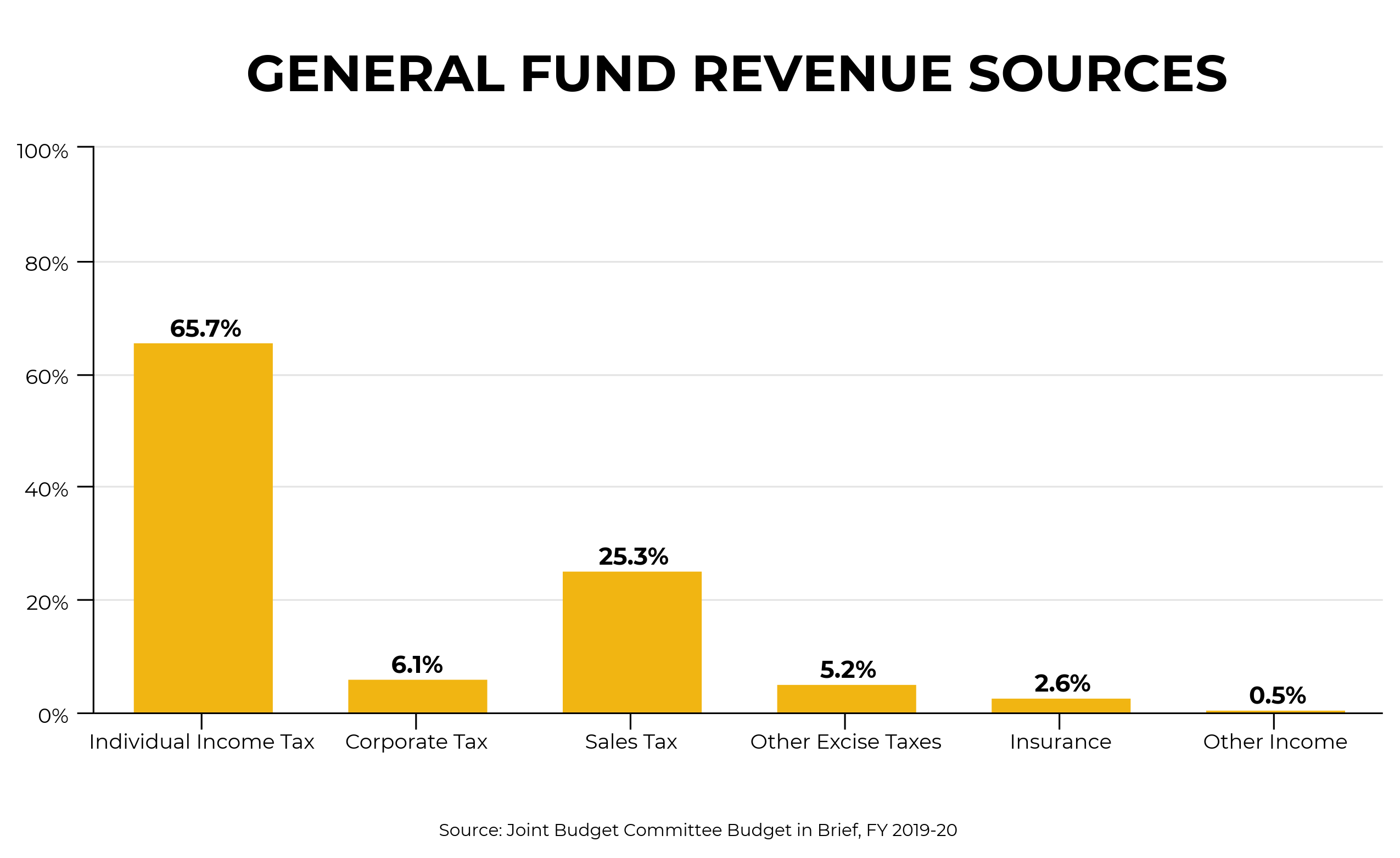

The General Fund is composed of various taxes paid by Coloradans. The largest portion of taxes are income taxes (65.7 percent of the FY 2019-2020 budget) and sales taxes (25.3 percent). Other sources include corporate income taxes, excise taxes — like retail marijuana, liquor, and tobacco taxes — and insurance. There is also about $681 million of the $9 billion collected in income and corporate taxes that goes to the State Education Fund and is locked there. The six agencies that receive the highest totals of General Fund dollars — as illustrated in the chart above — include:

The six agencies that receive the highest totals of General Fund dollars — as illustrated in the chart above — include:

- Department of Education

- Department of Health Care Policy and Financing

- Department of Higher Education

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Corrections

- Judicial Department

Health care is by far the largest total budget item. This makes sense given the context of the last decade, as there have been significant policy decisions made at both the federal and state level to increase the availability and affordability of health insurance. This, along with increases in health insurance costs, have increased the budget for health care in the state.

Various constitutional obligations create a process that means even a lot of General Fund dollars are spoken for.

Colorado voters passed Amendment 23 in 2000, creating new mandates around K-12 education spending. For the first 10 years Amendment 23 was in effect, spending on education had to be increased by at least inflation plus 1 percent. After those 10 years, beginning in FY 2011-2012, spending had to increase by just inflation. That has created increased obligations for the budget over the years.

The formulas involved for education spending — per-pupil spending must be at a certain level and then school districts get increased funding based on other factors, like the number of at-risk students and the area’s cost of living — mean this portion takes up a large part of General Fund revenue. If just looking at per-pupil funding without considering any other factors used to determine which districts receive more money, that would be the vast majority of the Department of Education funding budget. For example, in 2017-2018, the per-pupil funding formula mandated the General Assembly to provide $5.7 billion of the $6.6 billion in total funding.

There are other constitutional measures that tie up funding within the General Fund that must be accounted for. The Old Age Pension was approved as part of the constitution by voters in 1936 and was amended in 1956. It provides assistance for needy Coloradans aged 60 years old and above. It comes from the General Fund, and totaled slightly more than $86 million in FY 2018-2019.

What these various obligations prove is while some might bemoan the high price of the Colorado budget, there is only so much discretion for lawmakers to adjust funding levels.

While $32 billion sounds like a lot of money, Colorado is hardly swimming in discretionary money. Lawmakers must make some very hard decisions with less money than assumed. For example, based upon the Legislative Council economic forecast in June 2019, there was about $338 million left over from the previous budget, while factoring in inflation and population growth. These decisions are then made more difficult by the presence of a revenue cap on the amount they can actually use for Coloradans. Knowing the state has to pay a large amount to K-12 education through funding obligations, match certain federal funding for health care, as well as spend on corrections (prisons and jails) and the judicial system, there is very little prioritization that can happen outside of individual agency budgets.

When critics of Colorado’s government say lawmakers need to prioritize budgetary spending, they are not necessarily wrong, but they are confusing the issue. Yes, Colorado needs to prioritize where it sends funding within the state government. And yes, lawmakers certainly do that. Many programs just don’t get adequate funding because the money simply isn’t there. Instead, Colorado needs to raise more revenue through changes in the tax code so all Coloradans can feel the gains in the economy.