Despite a Strong Economy, Colorado Wages Barely Outpaced Inflation in 2018

Colorado’s economy is strong and continues to grow. We added over 65,000 jobs in 2018, our unemployment rate was 3.5 percent in March 2019, and averaged 3.3 percent in 2018. Our total state personal income, a measure of our overall economy, grew by 5.7 percent in 2018, the fourth highest in the nation. Given these positive measures, why do so many Coloradans feel squeezed economically?

Recent wage data released by the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE) provides some insights. It shows median wages in Colorado grew by 3.5 percent, going from $19.66 per hour in 2017 to $20.34 in 2018. Not too shabby.

Related: 5 Economic Trends to Watch in 2019

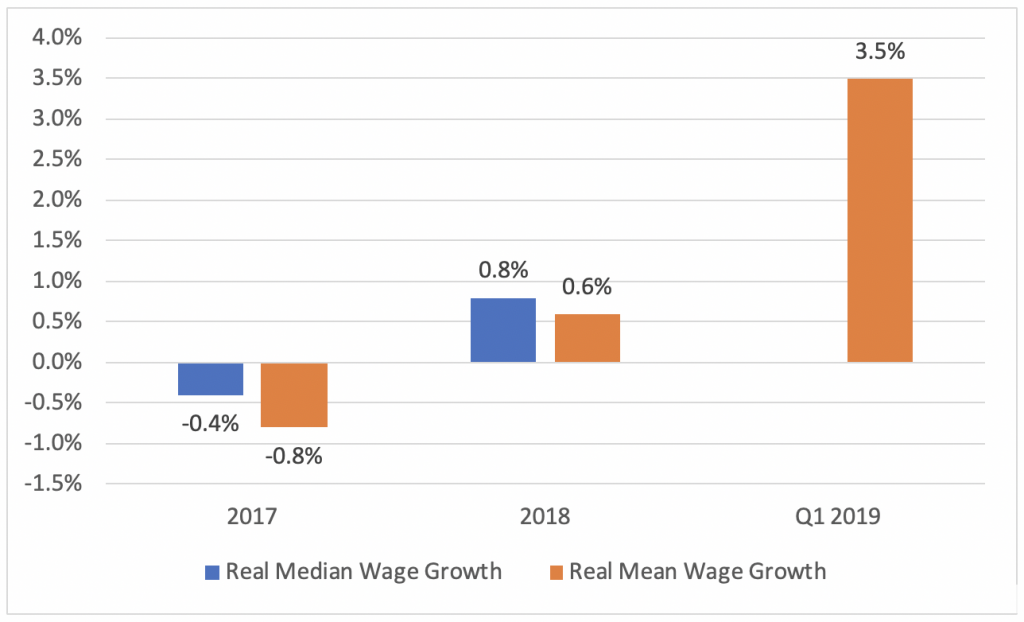

But when we adjust for Colorado’s 2.7 percent inflation rate during 2018, we find the inflation-adjusted “real” wage growth was only 0.8 percent, leaving most Coloradans struggling just to keep up with rising prices. This comes on top of 2017 when real median wages declined by 0.4 percent after the state’s 3.4 percent inflation rate wiped out the 3 percent growth in wages.

Things are looking better in the first quarter of 2019 when, according to CDLE data, mean average wages grew by 5.8 percent, outpacing the state’s 2.3 percent inflation rate, resulting in 3.5 percent real growth. By comparison, inflation-adjusted mean average wages declined by 0.8 percent in 2017 and grew by 0.6 percent in 2018.

Real Wage Growth in 2017, 2018, Q1 2019

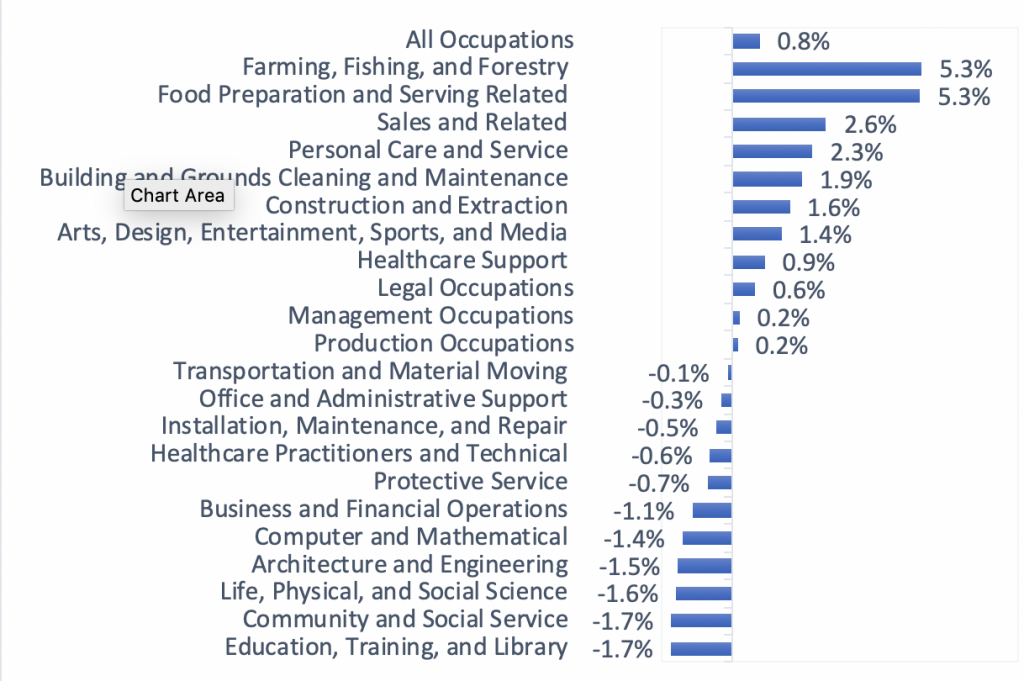

Wage Growth for Specific Occupations

A more detailed analysis of the broad occupational groups in Colorado shows jobs paying low wages saw some of the largest wage growth in 2018. For example, of the 11 occupations with positive real wage growth in 2018, seven had median wages below the statewide median. The two groups with the largest real wage growth — farming, fishing and forestry and food preparation and serving — had median wages of $13.74 and $11.39 per hour, respectively. These and the other low-wage occupations benefited from the increase in Colorado’s minimum wage from $9.30 to $10.20 per hour in 2018.

Management and computer and mathematical occupations, the two highest paying occupations at $56.15 and $45.06 per hour, had real wage growth in 2018 of 0.2 and -1.4 percent, respectively.

Real Growth in Median Wages by Occupation, 2017 to 2018

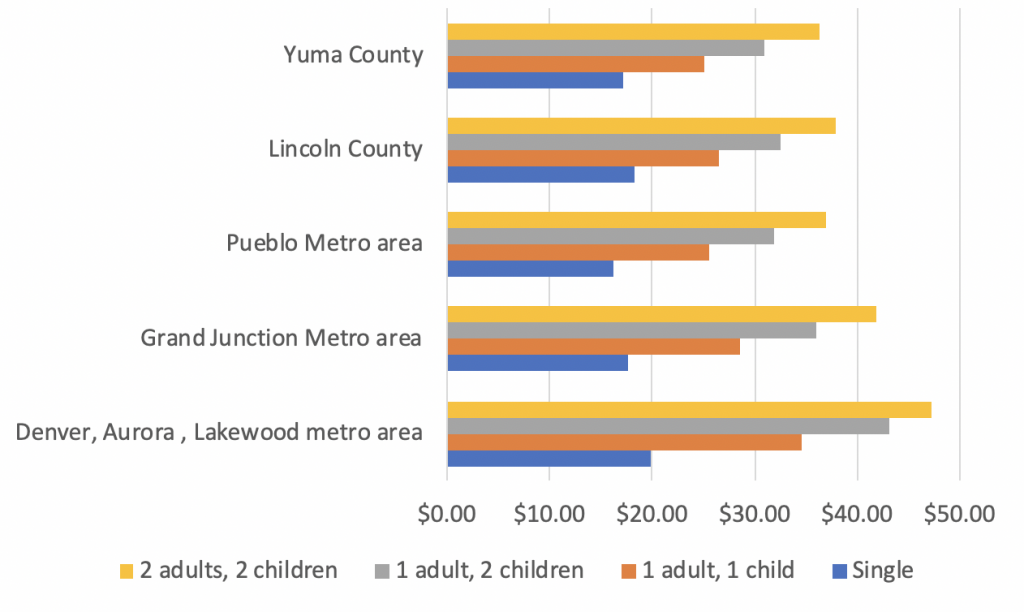

However, even though they had larger real wage increases the lowest wage jobs barely pay enough to support a single worker, let alone help a family get ahead. According to the EPI Family Budget Calculator, it took $19.81 per hour to support a single worker at a modest level in the Denver-Aurora-Lakewood metro area in 2017. Even in lower cost areas, these low-wage jobs do not pay enough to cover the cost of living. For example, it took $16.16 per hour to support that same worker in the Pueblo metro area, and $17.22 per hour in Yuma County on the Eastern Plains.

A single parent with one child would need to earn hourly wages of $34.60 in the Denver metro area, $25.48 in the Pueblo metro area, and $25.15 in Yuma County just to make ends meet.

Hourly Wages Needed to Support Various Family Types in Selected Colorado Communities in 2017

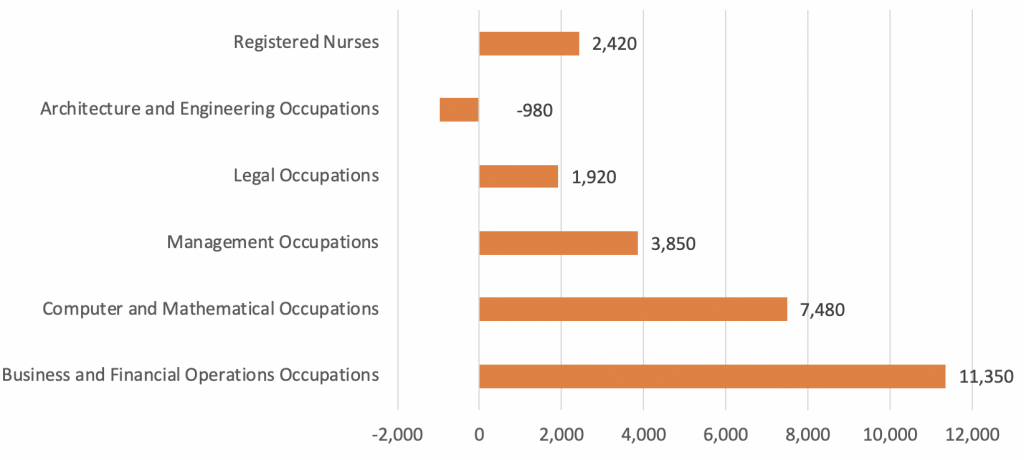

Number of Higher Paying Jobs Grows

One of the positive takeaways from this data is more higher paying jobs are being added than lower paying ones. Of the four occupations that account for half of all the jobs created in 2018, three pay more than Colorado’s median wage, two of them significantly more, and only one pays less. One of the lowest paying occupations, sales and related occupations, which pay a median hourly wage of $14.82, saw the largest decline in 2018 losing 4.23 jobs over 2017.

Higher paying jobs are also growing at a faster pace. Legal occupations grew the fastest in 2018, up 9.3 percent over 2017. These jobs pay a median wage of $41.59 per hour, double the $20.34 statewide median wage. When we compare the six occupations with the fastest growth rates — accounting for 51 percent of all jobs created in 2018 — to the statewide median wage we find two pay twice as much, one pays two-thirds more, one pays about the same, and two pay between 20 percent to 40 percent less.

In our report, Colorado Middle Class Families: Characteristics and Cost Pressures, the Bell identifies jobs most likely to pay middle class wages and those least likely to do so. More new jobs were added in occupations more likely to propel a family into the middle class than in jobs less likely to do so. The six occupations more likely to pay middle class wages grew by 26,040 jobs in 2018, accounting for 40 percent of all the jobs created in Colorado.

2018 Growth in Jobs Most Likely to Pay Middle Class Wages

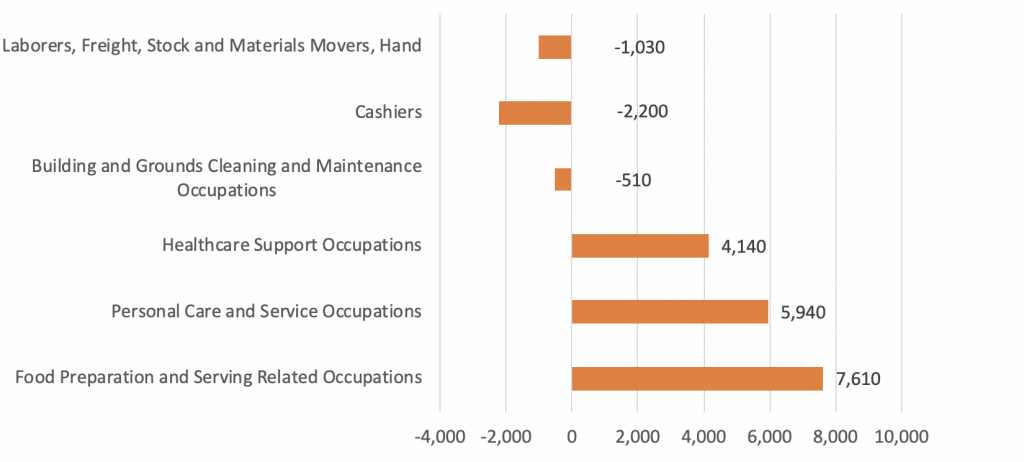

The six occupations least likely to pay middle class wages grew by 13,950 jobs, accounting for 21 percent of all the jobs created in Colorado in 2018. Three of these occupations lost a total of 3,740 jobs in 2018.

2018 Growth in Jobs Least Likely to Pay Middle Class Wages

With Unemployment Low & Economic Growth Strong, Why Aren’t Wages Growing Faster?

This question has vexed economists for the last several years. In the past, during periods of low unemployment and strong economic growth, such as the late 1990s, wages went up much faster than now. Nationally, wages grew by about 4.8 percent annually in the late 1990s, compared to 3.4 percent today. Below are four prominent theories put forth to explain why wages are growing more slowly now than in the past.

Labor Markets Aren’t as Tight as Unemployment Rate Indicates

Even though the unemployment rate is near a record low, there are many workers on the sidelines. Jared Bernstein, senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and former chief economist for Vice President Joe Biden, argues there is greater slack in the labor market than the unemployment rate would suggest. The employment rate for prime aged workers (25 to 54) dropped significantly during the Great Recession and has not returned to previous levels. As wages rise some of these workers come off the sidelines and join the workforce, which keeps wages lower than they would be without this pool of workers. For example, the share of Coloradans aged 16 and over participating in the workforce ranged from 70 to 75 percent during the economic boom of the late 1990s when wages grew more quickly than today. While the rate is rising it is 69 percent today.

Productivity Isn’t Growing as Fast as It Once Did

Jason Furman, chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisors in the Obama Administration and currently a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School, argues that lower productivity growth explains a lot of why wages are not growing as fast now. Wages and productivity pretty much grew at similar rates between the end of World War II until about 2000. Analysis by the Economic Policy Institute shows there has been a more limited relationship between productivity and wage growth in recent years. Even so, Furman argues productivity grew strongly in the late 1990s, but has been dismal in recent years. This drop in productivity leaves businesses with lower profits to pay higher wages.

Growing Imbalance in Power Between Workers & Employers

There has been a dramatic decline in unionization and an increase in the concentration of dominant employers in certain industries, giving the latter more power to set wages. In addition, many companies are using non-compete clauses in worker contracts to prevent workers, even those in low-wage jobs, from leaving to take a higher paying job with a competitor. Other employers are using staffing agencies and misclassifying workers as contractors to limit the wages paid to workers. There has also been a decline in labor standards, such as the eroded overtime rule. Bernstein and others argue these factors combine to make it more difficult for workers to negotiate for and receive higher wages, even in a tight labor market.

Workforce’s Changing Composition Makes Wage Growth Appear Lower Than It Is

The San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank argues as older, higher paid workers leave the workforce, they are being replaced by younger, lower paid workers. Plus, new entrants to the workforce, such as those lured off the sidelines by the hot job market or those moving from part-time to full-time work, generally earn less than the typical full-time worker. These factors combine to hold down the growth in overall weekly earnings by 1.5 percentage points to 2 percentage points, according the Fed’s analysis. Although individual workers might be earning more, the aggregate wages paid to all workers are lower, thus pulling down average wages and slowing the pace of wage growth.

The data presented by CDLE point to wages that continue to grow slowly compared to inflation, and show average workers aren’t benefiting as much as strong economic numbers might suggest. This also shows the need to keep working on measures, such as increasing the number of salary workers that automatically qualify for overtime, eliminating non-compete clauses in contracts, and strengthening the bargaining power of workers to ensure the strong economy promotes economic mobility for all Coloradans.