In a Recession, Prop 109 Leads to Higher College Tuition

While Colorado’s economy is currently strong and tax revenue is rolling in, it won’t always be this way. When the economy takes a turn, and it will, lawmakers will have to scramble to find money just to keep state operations going. If Prop 109 passes and the state sells $3.5 billion in bonds without additional funding, it won’t be so simple for lawmakers to “do their damn job.” In fact, it will be much more difficult, and the consequences of Prop 109 will fall squarely on the shoulders of everyday Coloradans like you and me.

Related: 2018 Colorado Ballot Guide

Before they can fund critical services such as education, health care, human services, and corrections, legislators must find $260 million to pay the bond holders of Prop 109. That’s not a one-time payment; those bond holders will be back every year to collect. They’ll go to the front of the line and will be paid before Colorado’s teachers, doctors, hospitals, and prison guards.

Related: Briefed by the Bell Hub

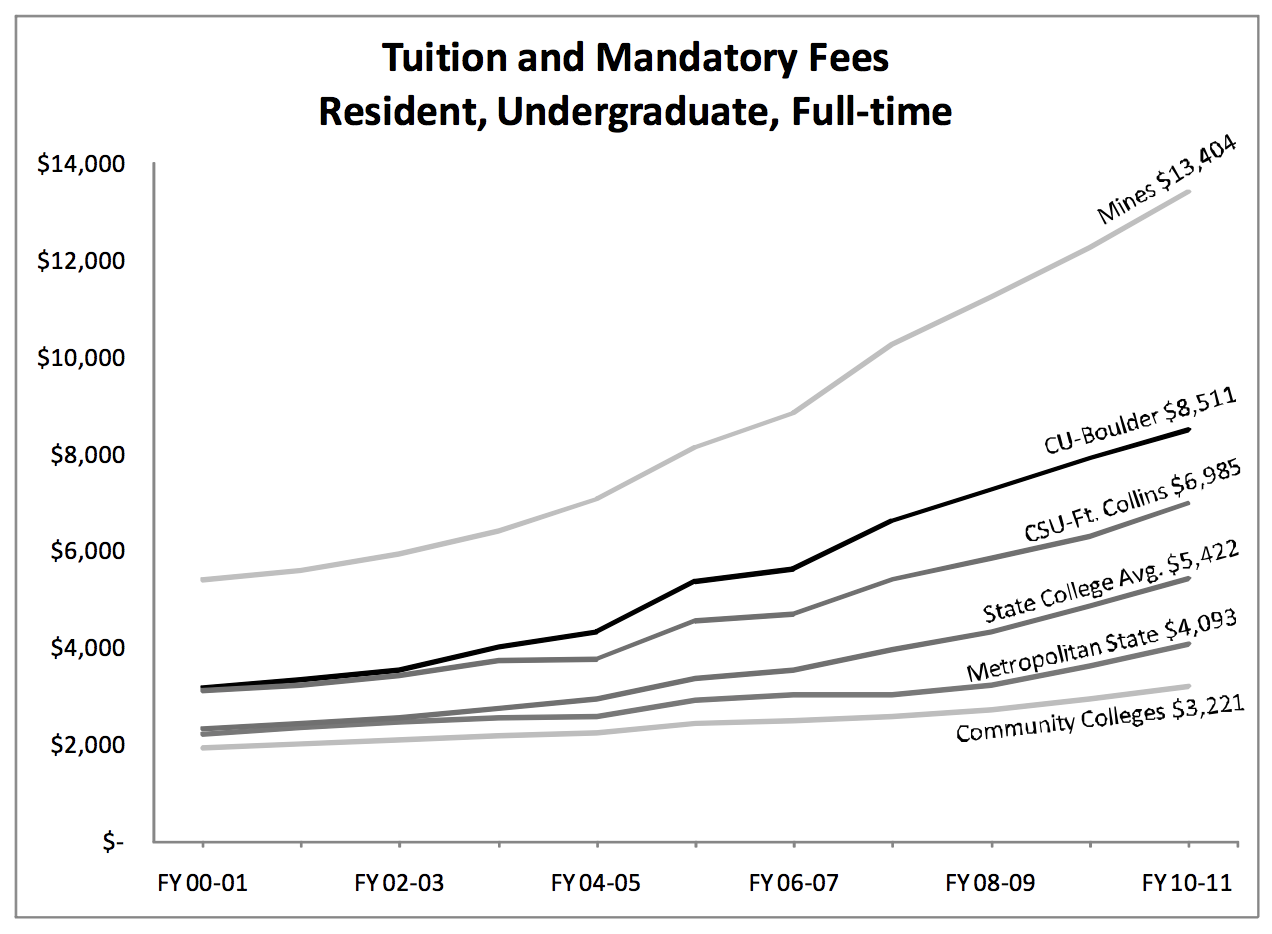

Who else will most likely lose when this happens and Prop 109 passes? Colorado’s college students and their families. When confronted with two devastating recessions in the 2000s, lawmakers balanced the state budget, in part, by cutting state funding for colleges and universities. To make up for the cuts, schools raised tuition.

What Happened to Tuition During Recessions of Early 2000s

Source: Colorado Joint Budget Committee, FY 2011-2012 Staff Budget Briefing, Department of Higher Education, Eric Kurtz, November 17, 2010

Source: Colorado Joint Budget Committee, FY 2011-2012 Staff Budget Briefing, Department of Higher Education, Eric Kurtz, November 17, 2010

During the Great Recession, Colorado cut funding for colleges and universities by $90 million to $320 million between 2008 and 2010. That led to tuition being raised by about 9 percent each year. It would have been even worse, except the federal government provided Colorado with over $620 million in ARRA funds to use for higher education. During the 2002-2004 recession, lawmakers cut funding for higher education by $206 million between FY 2002-2003 and FY 2003-2004. In 2003-2004, tuition went up by 15 percent at CU Boulder, while Colorado’s community colleges saw a 5 percent increase on average. No wonder student loan debt in Colorado soared by 331 percent between 2003 and 2017.

Related: Ready for Retirement & Still Grappling with Student Loan Debt

While the state takes in less money during recessions, college costs go up. That’s because more people go to school to get job skills and training when the economy turns downward, driving up the cost for faculty, advisors and general operations. To cover these costs, schools end up raising tuitions and fees.

When an inevitable downturn hits and state revenues head south, legislators will need to search high and low for funds to balance the budget, plus find an additional $260 million each year to pay Prop 109’s bond holders. To find the money to pull this off they will likely turn to a familiar source — college students and their families.