Colorado’s Middle Class Squeeze is Real

Colorado’s middle class is in trouble.

That’s according to CU Denver Professors Geoff Propheter and Todd Ely, who revealed their preliminary findings from a state-specific study focusing on Colorado’s middle class squeeze. During the CU School of Public Affairs’ First Friday Breakfast cosponsored by the Bell Policy Center and the Colorado Trust, we learned only dual-earner professional households can really keep their head above water.

Related: What Happened to Colorado’s Middle Class?

Debt is reemerging as a problem for the state’s middle class. Middle class debt is up 29 percent in total between 2000-2016 and, alarmingly, student loan debt is up 349 percent. Health care costs climbed 70 percent, while college costs creeped up 85 percent during the same time. Meanwhile, wages are only up 20 percent. Stagnant wages, combined with escalating costs are leading to the “middle class squeeze” being discussed nationally.

Propheter and Ely’s research also expand on who actually comprises Colorado’s middle class. The racial breakdown is stark: Whites make up more than 76 percent of the middle class and more than 82 percent of the upper class. By contrast, Hispanic families comprise 8.1 percent of the Colorado’s middle class and only 3.7 percent of its upper class, whereas black families’ share is 2.1 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively.

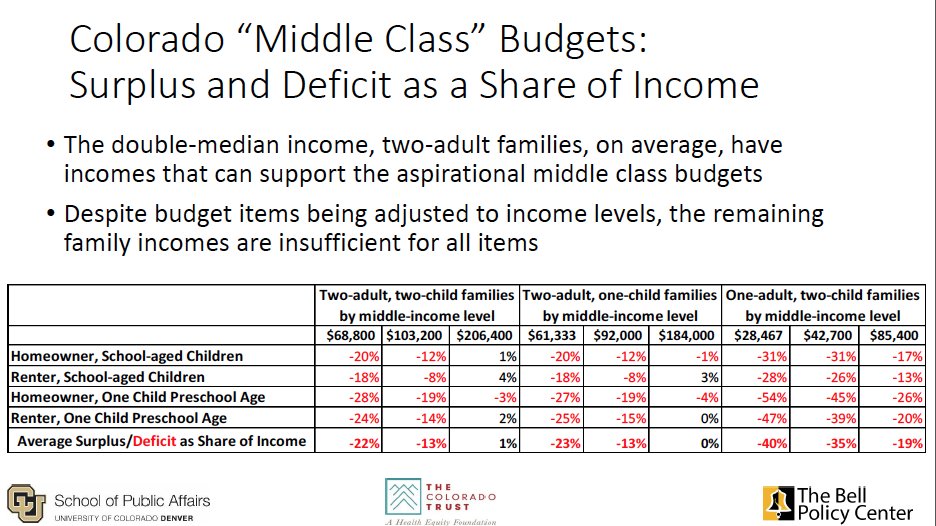

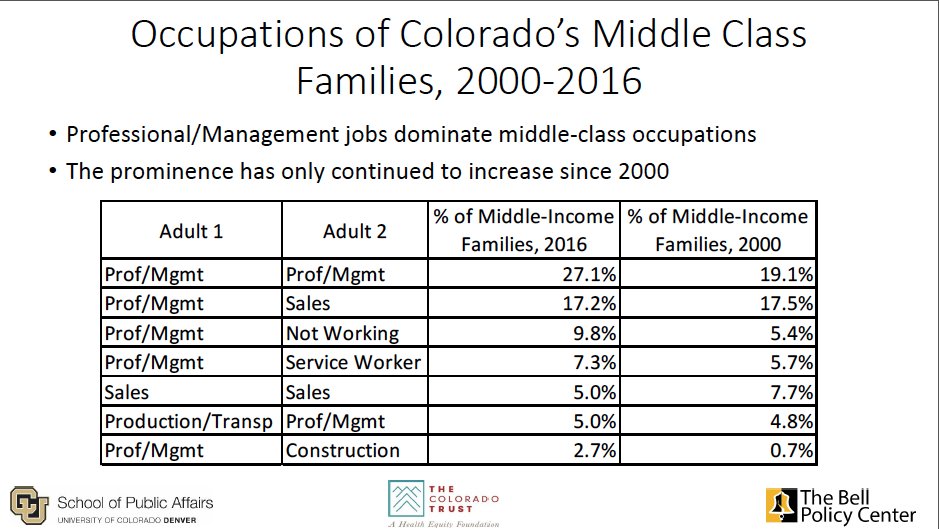

One of the more startling findings pertains to the type of job it takes to earn a middle class lifestyle in Colorado. The research shows the difficulty of being a middle class family on one income, showing middle class Colorado families overwhelmingly are made up of two working adults. As the findings from the CU Denver research show, both parents must be employed in some kind of professional or management job to join the middle class, but even with that, most middle class families still struggle to break even. This is because any analysis of the middle class must consider common expenses associated with a middle class lifestyle, including health care, retirement savings, college savings, homeownership, and taking an occasional vacation to unwind.

The Bell Policy Center and the Colorado Trust commissioned the study, which will be released in the early summer, after noticing a dearth of information about Colorado’s middle class. To date, only a handful of similar studies have been conducted.

With this research, we aim to learn the following about Colorado’s middle class:

- What does the middle class look like?

- Who is in the middle class?

- How have these answers changed since 2000?

Professors Propheter and Ely went through American Community Survey data — this is yearly data administered by the U.S. Census Bureau — and adjusted for family size, geography (urban vs. rural), and stage in life. It shows what many in Colorado already suspect: The middle class is shrinking. The middle class is becoming harder and harder to break into, and even more difficult to stay in without getting massive amounts of help, either through borrowing or shortcuts on spending habits.

What’s very clear: Colorado’s middle class needs help from policymakers. If a middle class lifestyle is dependent on two incomes, we must ensure child care is affordable. We need to invest in higher education so families don’t go broke trying to afford a college education. We need to make sure health care is affordable, as the CU Denver study finds health care as the most essential budget item for a middle class family. A portable retirement savings program will help families save for the future in a fiscally responsible way. And of course, we need to raise wages through many avenues like pay equity, paid leave policies, and raising the overtime salary threshold. If Colorado families need two parents working to achieve a middle class life, it’s crucial both men and women earn a fair wage for their work. Acting on policies to make this possible is well within Colorado policymakers’ bailiwick.

Focusing on these bedrock ideas to make getting into and staying in the middle class more attainable, we can improve the lives of many across Colorado. The question now: Will state leaders do their part?