Student Debt Dashes Hopes for Homeownership

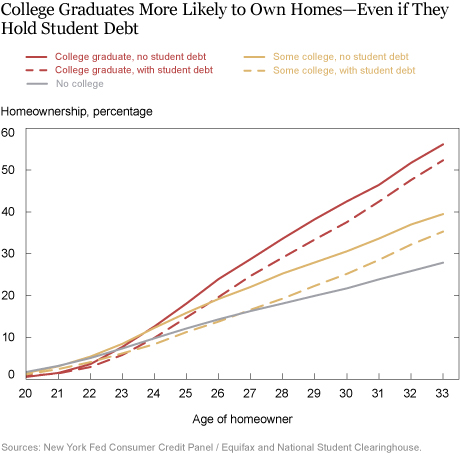

Earning a postsecondary credential has significant positive outcomes for economic well-being and opportunity later in life, among these is homeownership. But new data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows individuals with student loan debt are less likely to own a home in their early thirties than those who completed their education without taking on as much – or any – debt.

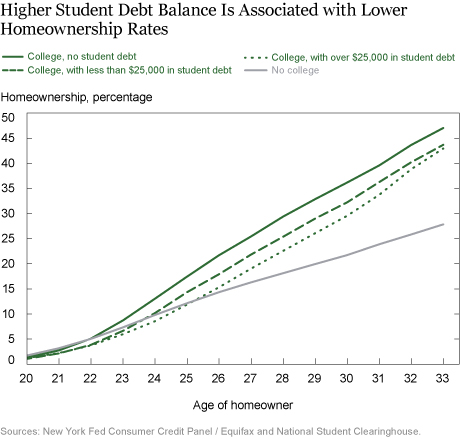

For any type of degree (bachelor’s or associate’s), those who completed a post-secondary program had the highest homeownership rates over time, regardless of whether they held student debt or not. But the Fed’s research also finds the amount of student debt an individual holds does, in fact, affect the likelihood of homeownership. Those holding more than $25,000 in debt by age 30 are generally less likely to own homes than those with smaller amounts of debt. The $25,000 cutoff point was selected by the Fed to represent the average debt level observed among borrowers in its study.

Given these findings, data on student loan debt outcomes for Colorado graduates take on new and more urgent meaning. The Colorado Department of Higher Education reports 67.4 percent of students graduating with a four-year bachelor’s degree from a Colorado public institution hold debt, and the average debt is $25,877.

The national figures for four-year graduates are 60 percent and $26,800, respectively. The Center for Responsible Lending says graduates of Colorado’s for-profit four-year institutions owe, on-average, $32,452. Clearly, based on these figures, many Colorado students have debt levels that reduce their opportunities for homeownership, which in turn has long-term consequences for these individuals, their families, and our state.

The Fed notes its findings are vital because “homeownership represents an important means of wealth accumulation, with housing equity being the principal form of wealth for most households.” It also stresses “changes in the way we finance higher education, with an increased reliance on student debt, may have important implications for the housing market and the distribution of wealth.”

The Fed notes its findings are vital because “homeownership represents an important means of wealth accumulation, with housing equity being the principal form of wealth for most households.” It also stresses “changes in the way we finance higher education, with an increased reliance on student debt, may have important implications for the housing market and the distribution of wealth.”

Due to significant declines in state postsecondary education funding over the last several decades, the researchers say students and families are now on the hook for increased tuition and other costs. A recent report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities points out “nearly every state has shifted costs to students over the last 25 years,” but Colorado is among the top states in its reliance on students and families to fund its public post-secondary institutions rather than through public dollars. This shift has in turn led to increased reliance on student loans to help cover these costs.

We have repeatedly warned – most recently in our 2017 Opportunity Handbook – this post-secondary education cost shift is unsustainable and has negative consequences for opportunity, especially for those aspiring to enter or stay in the middle class. The shift has been particularly hard on low- and middle-income families because, while college costs in Colorado increased by 102 percent between 2000-2001 and 2014-2015, average household income only rose by 0.31 percent over the same period, when adjusted for inflation.